Vulnerability Details

Product: Everest Backup plugin for WordPress

Affected: v2.3.5 and older

Patched: v2.3.6

Vendor: Everest Themes

CVE: CVE-2025-11380

Introduction

Recently I started learning more about auditing WordPress plugins for security vulnerabilities. WordPress plugins are a specific, niche area of security research but WordPress’ popularity means there are plenty of plugins to target. Multiple resources exist to help a newcomer get started including a great GitHub repository maintained by a WordPress security company called WordFence. The repository provides a brief overview of risky behavior to look for. I highly recommend checking it out if you are interested in a broader overview of WordPress plugin security: https://github.com/wpscanteam/wpscan/wiki/WordPress-Plugin-Security-Testing-Cheat-Sheet

I strongly believe that one of the best ways to learn something is to start doing it! Using the WordPress guide as a starting point, along with reading disclosed vulnerability reports for other WordPress plugins, I started looking at WordPress plugins for security issues. I focused my research on plugins related to site backups as a bug in backup functionality could potentially allow access to the parent site’s data via backed up copies.

Today’s post highlights a vulnerability I found in the Everest Backup plugin.

Background

Before we dive deep into vulnerability details, lets start with a quick overview of WordPress architecture to provide context.

WordPress and its plugins are written in the PHP programming language. When installing WordPress on a web server, it creates multiple directories in the web root to hold site files. Plugins themselves are installed on a WordPress web server in the wp-content/plugins/ directory. Each plugin is installed into its own folder and the code for a given plugin is available for review inside its folder.

WordPress relies heavily on hooks to run code at different stages of a website’s load lifecycle. For example, some hooks run at the start of processing a new browser request, some hooks run after a user logs in, and so forth.

WordPress, like most modern frameworks, uses a browser feature called Asynchronous Javascript And XML, or Ajax for short. Ajax allows a webpage to send requests to its’ parent web application without reloading the entire page. Ajax allows websites to implement dynamic content, such as updating the progress bar for a long running process, without the user refreshing the entire page.

WordPress offers a hook which runs when the frontend web page makes an Ajax request to the WordPress site. Plugins can use this hook to implement dynamic content. The Ajax hook is triggered when a request is sent to /wp-admin/wp-ajax.php on a WordPress site.

A plugin can register an Ajax hook using the syntax add_action("wp_ajax_*", "function_name"); or add_action("wp_ajax_nopriv_*", "function_name");. The * portion of the wp_ajax_ string is chosen by the developer and can be any arbitrary string. This value is passed to WordPress during the Ajax request and tells WordPress to trigger this particular Ajax hook. The value allows WordPress to distinguish different Ajax hooks registered by different plugins or registered by the parent WordPress site framework.

The prefix wp_ajax_nopriv means the hook does not require user authentication while the prefix wp_ajax means it does require authentication. WordPress is fundamentally blog management software and expects most site visitors to be unauthenticated. Plugins have the option of using wp_ajax to prevent unauthenticated actors from interacting with that particular Ajax hook.

When sending an Ajax request to WordPress, the browser does not include the wp_ajax or wp_ajax_nopriv prefixes. For example, if a hook was registered with the string wp_ajax_nopriv_do_action, then the browser would send the Ajax request with hook name do_action.

The “function_name” string is the name of a PHP function within the plugin. WordPress executes the code in the function after receiving the incoming hook.

Vulnerability Walkthrough

Now that we have some background information on WordPress Ajax hooks, let’s dive into the Everest Backup plugin’s vulnerability.

Everest Backup includes a code file installed in the plugins’ home directory at wp-content/plugins/everest-backup/inc/classes/class-ajax.php. Inside this file, the plugin’s constructor function registers multiple Ajax hooks including one called wp_ajax_nopriv_everest_process_status. The snippet of code which registers this hook is shown below and the specific line of interest is highlighted.

public function __construct() {

...<snipped>...

add_action( 'everest_backup_before_restore_init', array( $this, 'clone_init' ) );

add_action( 'wp_ajax_nopriv_everest_process_status', array( $this, 'process_status' ) );

add_action( 'wp_ajax_everest_process_status', array( $this, 'process_status' ) );

add_action( 'wp_ajax_nopriv_everest_backup_cloud_available_storage', array( $this, 'cloud_available_storage' ) );

add_action( 'wp_ajax_everest_backup_cloud_available_storage', array( $this, 'cloud_available_storage' ) );

...<snipped>...

}The first thing we notice is this Ajax hook can be triggered without authentication, as seen via the prefix wp_ajax_nopriv.

The second thing we notice is it calls the function “process_status”. This is the code that runs when the hook fires. Checking that function shows the following code:

public function process_status() {

wp_send_json( Logs::get_proc_stat() );

}The function calls wp_send_json() with the return value of the Logs::get_proc_stat() function. The function wp_send_json() is a built-in WordPress function and it returns JSON formatted data to the web browser. The plugin thus appears to return JSON data in the HTTP response, but we don’t know what this data is yet.

The get_proc_stat() function of the Logs class looks like the following:

public static function get_proc_stat() {

$file = EVEREST_BACKUP_PROC_STAT_PATH;

if ( ! file_exists( $file ) ) {

return array();

}

$log = @file_get_contents( $file );

return $log ? json_decode( $log, true ) : array();

}The code attempts to open a file at the path represented by the $EVEREST_BACKUP_PROC_STAT_PATH variable and returns the contents.

The code at inc/constants.php defines this variable as:

/**

* Path to PROCSTAT file.

*/

define( 'EVEREST_BACKUP_PROC_STAT_PATH', wp_normalize_path( EVEREST_BACKUP_BACKUP_DIR_PATH . '/.PROCSTAT' ) );So we know the filename is .PROCSTAT and it’s apparently in the EVEREST_BACKUP_BACKUP_DIR_PATH folder. The contants.php file happens to define this one as well:

/**

* Directory path to backups folder.

*/

define( 'EVEREST_BACKUP_BACKUP_DIR_PATH', wp_normalize_path( WP_CONTENT_DIR . '/ebwp-backups' ) );The WP_CONTENT_DIR variable is a WordPress variable and it refers to the location of the wp-content/ directory common to all WordPress sites.

So, putting it all together, the wp_ajax_nopriv_everest_process_status hook reads the contents of wp-content/ebwp-backups/.PROCSTAT and returns it as the HTTP response in JSON form.

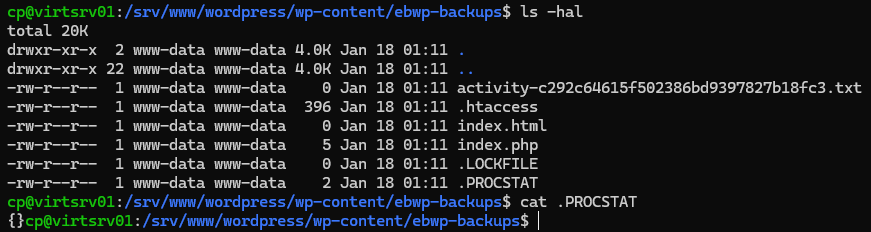

But, when we check the file on our test webserver, it appears to be mostly empty:

The only content in the file is an empty JSON object {}.

Without data in the file the hook did not seem terribly useful. I made a note of it and continued analyzing the plugin elsewhere.

I have found in my experience that static and dynamic (or runtime) analysis compliment each other. A good security check looks at software using both methods. The next step of analysis was thus to start using the plugin and observe it in action.

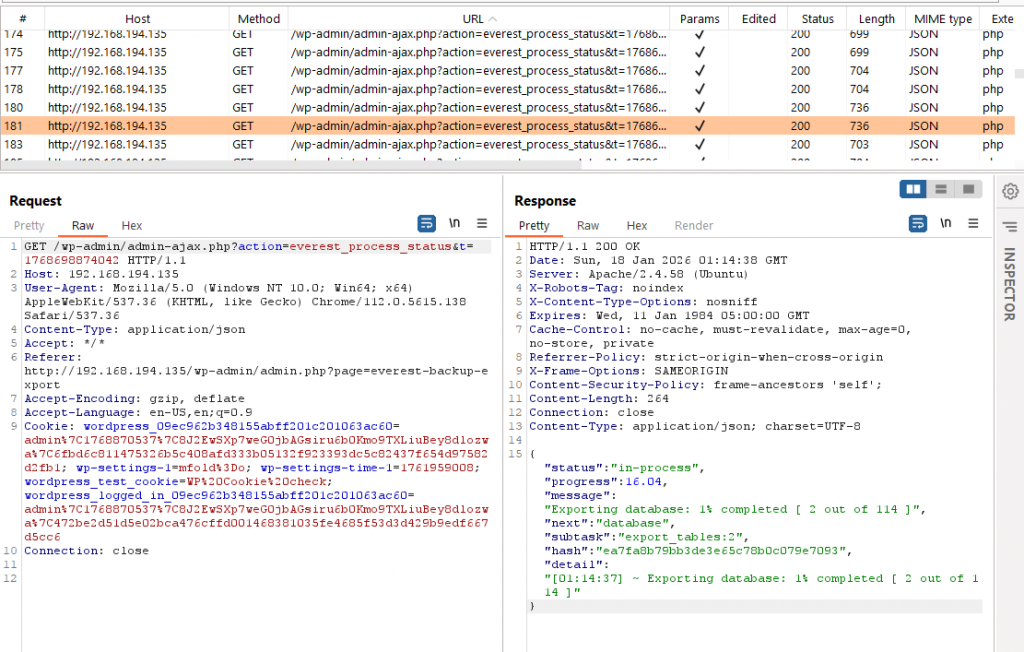

I setup the plugin and triggered a test backup. Once the backup completed, I went to Burp Suite’s HTTP history tab and noticed a large number of Ajax requests. Reviewing the Ajax requests showed they were triggering the wp_ajax_nopriv_everest_process_status Ajax hook.

Notice the value of the “action” GET query parameter is set to “everest_process_status”. This corresponds to the hook we saw earlier in code. Recall that the browser does not send the wp_ajax_nopriv prefix part of the hook name, so the effective hook processed on the backend is wp_ajax_nopriv_everest_process_status.

The browser sends cookies with requests when it has cookies available for that site, which is why cookies appear in the screenshot. Cookies and thus authentication are not actually required for WordPress to process this Ajax request because the hook name is prefixed with wp_ajax_nopriv.

Static review seemed to show the hook returned the contents of a file that did not exist, but here the hook returns data. What gives?

As it turned out, the Everest plugin’s backend code, responsible for creating a backup, would write a backup job’s status at regular intervals into the .PROCSTAT file once a backup job was started. The Ajax hook would read the file and return it to the frontend code, which would use the data to show the user the current backup job status. When the backup job was completed, the Everest plugin deleted the file.

This explains why no file existed during static analysis – the .PROCSTAT file only exists during an active backup operation.

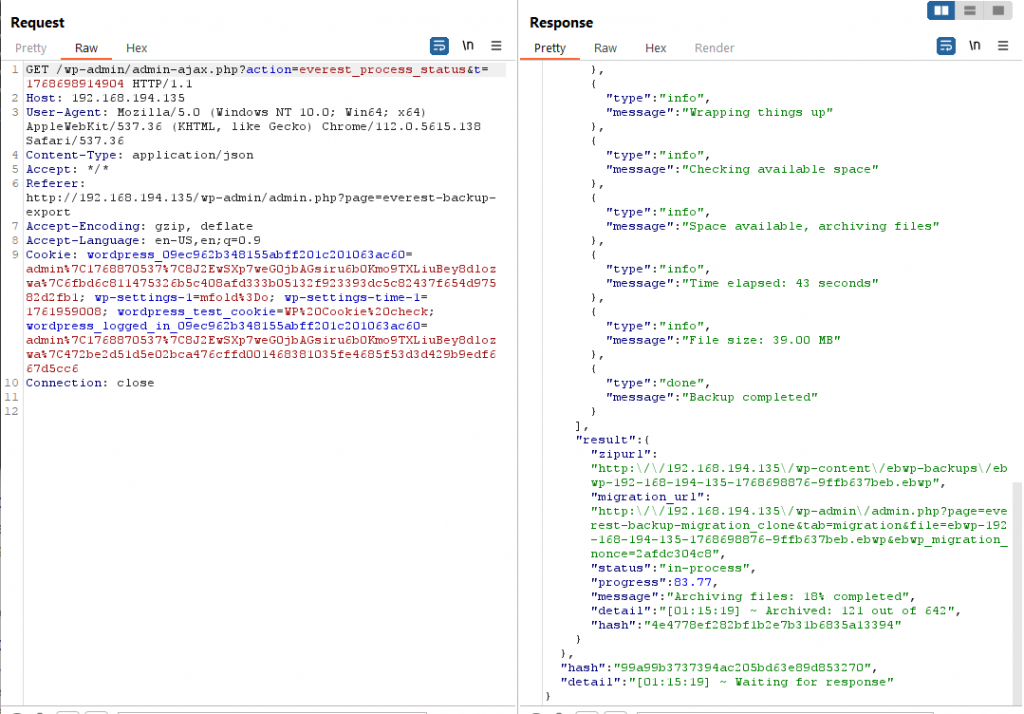

Scrolling through the results in Burp Suite showed the returned data changed toward the end of the backup job. Everest Backup would return the filename of the backup along with a handy link to download it.

Backups were written to the folder /wp-content/ebwp-backups/. This directory is accessible to external visitors by visiting http://examplesite.com/wp-content/ebwp-backups/. Listing this directory’s contents is blocked, but an external visitor can download files in the folder provided the visitor knows the exact filename to request. No authentication is required to download a backup.

The filename included randomness to ward off brute force or guessing of backup filenames, but with the filename disclosed to unauthenticated Ajax calls, it became a security vulnerability. An external, unauthenticated attacker could continuously send Ajax requests to this Ajax hook. Once a backup job starts, the attacker could obtain the backup’s filename at the end of the job and then download it.

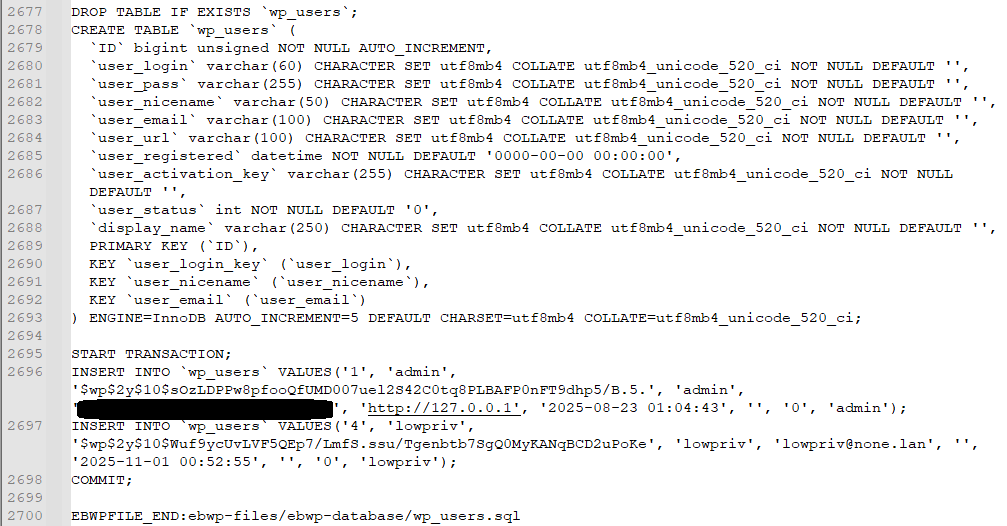

I tested the free version of Everest Backup and it does not provide functionality to encrypt backups (the paid version does though). Downloading the backup file is sufficient to obtain a copy of the WordPress site database. This includes all site data but also includes password hashes which could be subject to offline cracking attacks.

A proof of concept script is available on GitHub at https://github.com/fleetcaptain/everest-backup-cve-2025-11380.

Remediation

WordFence offers responsible disclosure assistance for WordPress plugins. With the sheer number of plugins, getting in contact with a given developer can be difficult, but WordFence works with the WordPress plugin repository to contact developers and take action if developers do not respond. WordFence also operates a bug bounty program for WordPress plugins although this vulnerability did not qualify for the program.

I reported the vulnerability to WordFence on September 21st, 2025. They worked with the developer to get it fixed and issued CVE-2025-11380. The vulnerability was patched with the release of version 2.3.6.

Thanks for reading and take care!